There’s an old adage that you can choose your friends but you can’t choose

your family. Well, that’s kind of true, although many people decide to cut

themselves off from family, either individual family members or the full

breakfast. But how about the communities we participate in? I’m not talking

about that vague (non)entity sometimes described as ‘the Community,’ but the

many separate, intersecting and concentric circles in which we move, live and

breathe, and which, to a greater or lesser extent, make us what we are.

Jews are often characterised, sometimes negatively stereotyped, as belonging

to a community that is not only close but closed. The ultimate exclusive

private members club, we seem to make little effort to welcome those who want

to join, even holding a tradition that a rabbi should make three attempts to

dissuade a potential convert. And that’s before they can even be considered for

acceptance as a pilgrim on the long and sometimes arduous journey towards

membership of the Jewish People

Including inclusivity from the start

And so it might seem surprising that in the long series of speeches by the

prophet Moses that make up the biblical Book of Deuteronomy (or Devarim),

one particular passage stands out as flying in the face of this cherished

exclusivity. In fact, Moses makes the boundaries of the community seem so

permeable, or should I say expansive, as to seem to disappear

altogether.

You stand this day, all of you, before the Eternal your God — your

tribal heads, your elders, and your officials, every householder in Israel,

your children, your wives, even the stranger within your camp, from woodchopper

to waterdrawer— to enter into the covenant of the Eternal your God, which the

Eternal your God is concluding with you this day, with its sanctions;

in order to establish you this day as the people of the Eternal, and in order

to be your God, as promised you and as sworn to your fathers Abraham, Isaac,

and Jacob. I make this covenant, with its sanctions, not with you alone, but

both with those who are standing here with us this day before the Eternal our

God and with those who are not with us here this day. (Deuteronomy

29:9-15)

Granting Rashi his interpretation of the ‘woodchopper’ and the ‘waterdrawer’

as being male and female servants respectively and noting that the phrase ‘the

stranger within your camp’ includes pretty much everyone else, we have a covenantal

community made up of…well…everyone. God is making a deal with men and

women, adults and children, tribal elders and plebeians, priests and laypeople,

Israelites and resident aliens – all and sundry.

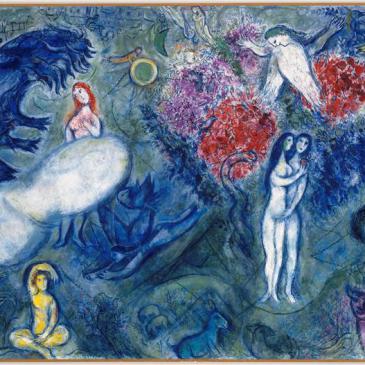

Far from a homogenous, ethnic monoculture, this people is, to use the Hebrew

phrase, an erev rav or ‘Mixed Multitude’, a phrase used in Exodus 12: 39 to

encompass those who were not Hebrews, but who made their own escape from Egypt,

perhaps taking advantage of the chaos when Pharaoh allowed Moses to lead the

Israelites out of Egypt. And just in case anyone’s missing from the list, the

passage throws in not just those standing there that day but those who are not

with them that day. Logically, that would seem to include absolutely everyone

who exists, ever existed or ever will exist – although commentators have

interpreted it as meaning specifically that the covenant is binding on those of

the People of Israel born later, in other words all of the descendants of

Jacob, both biological and spiritual up to the present and beyond.

Far from exclusive, we have Moses, arguably the founder of Jewish faith,

opening the floodgates to pretty much anyone who wants to come to the party, so

long as they accept that in doing so they are equally bound by all the terms

and conditions, whether they have ticked the box or whether they have not

ticked the box. All they have to do is to decide to show up and stand with the

people before God. Stand with us and you’re in.

According to Rabbi Sheila Shulman in her sermon ‘All of You’, it is this

‘decision, on the deepest level, to include herself or himself in, or not’ that

determines whether a person is part of the Jewish Community – Klal Yisrael.

It is not down to presumed gatekeepers, who may wish to exclude, for

example, converts, LGBT people or patrilineal Jews, but ultimately the

individual themselves who by ‘deciding with their whole being that he or she is

part of [the Jewish People], by linking up their whole being to the history,

the experience, the continuing life, of this unique people.’ By emphasising a

sense of ‘oneness; as uniqueness rather than homogeneity,

Rabbi Shulman opens up the seemingly paradoxical idea that diversity is a

condition for unity rather than an obstacle to it. After all, why even mention

‘unity’ if we are talking about a set of identikit members?

Or course divisions inevitably give rise to disagreement, discussion and

debate – all forms of discourse and deliberation to renew and replenish the

community’s mores and culture. But what should be a community’s attitude to the

alienated member, who at once both attempts to exclude others while refusing to

participate in the deliberative process? Should we try to include the person

who seems only to desire exclusion, both of others and, if only unconsciously,

themselves?

Tolerating the intolerant

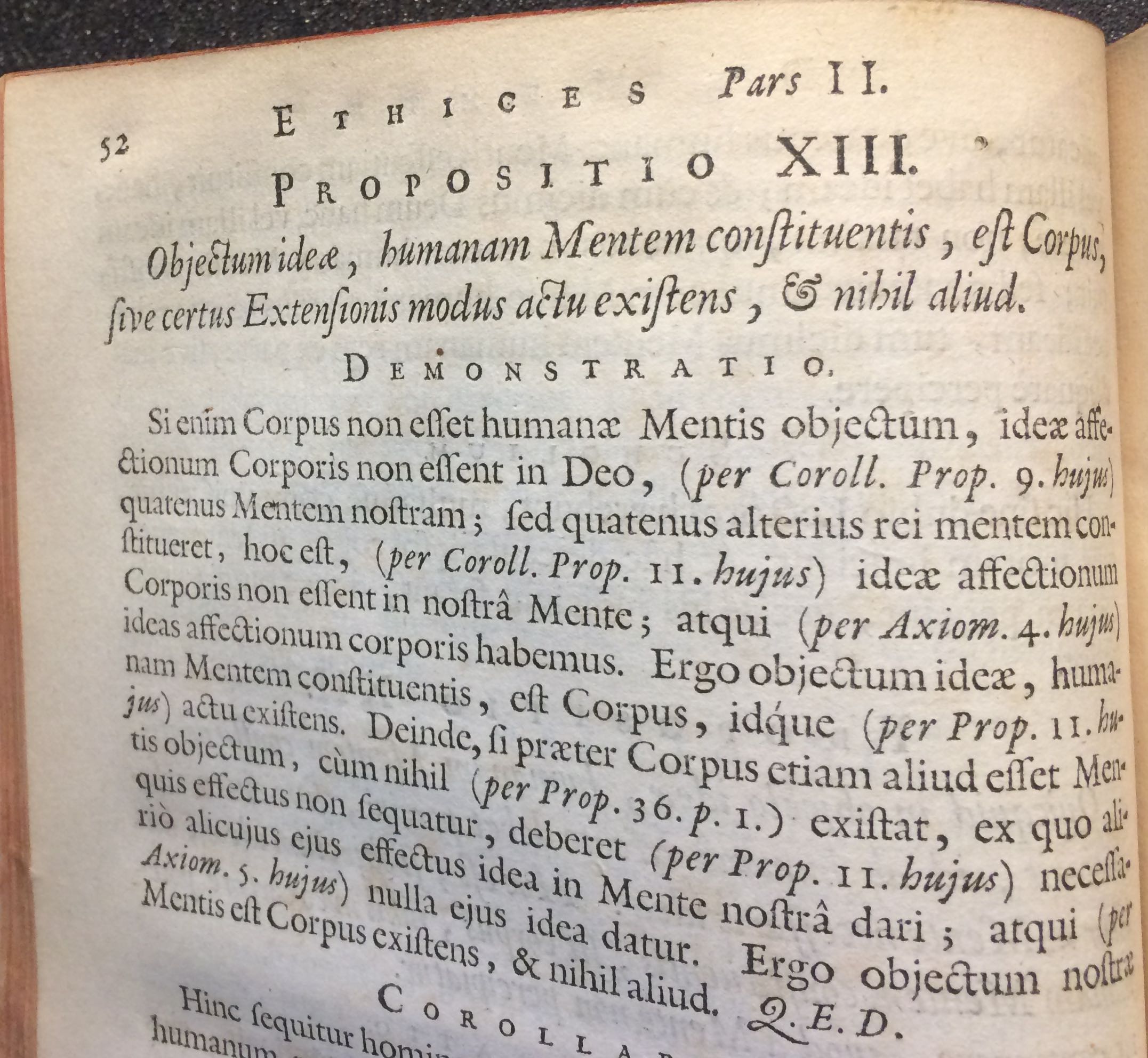

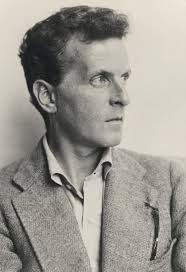

This problem is related to the famous (or infamous) Paradox of

Tolerance. In what might be one of the most influential footnotes in

intellectual history, the philosopher Karl Popper

questioned the liberal belief that all strands of opinion should be tolerated

in a free society. As a side remark to his exegesis of Plato’s critique of

democracy, Popper writes:

Less well known is the paradox of tolerance: Unlimited tolerance must

lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even

to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant

society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be

destroyed, and tolerance with them. – In this formulation, I do not imply, for

instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant

philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them

in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we

should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may

easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational

argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers

to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to

answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefor

claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We

should claim that any movement preaching intolerance and persecution as

criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to

kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.

(The Open Society and Its Enemies)

Although we might baulk at the criminalisation of movements, presumably only

on the basis of their ideology, it should be remembered that Popper, an

Austrian with Jewish ancestors who lived through the rise of the Nazis and the

Second World War, had witnessed the dangers of a laissez-faire

approach, the so-called ‘market place of ideas.’ To stretch this economic

metaphor, Popper seems to be stating a principle analogous to Gresham’s Law,

that bad money – or in this case bad ideology – drives out good.

Inclusive values

In a community, such as a synagogue, which does not have the mechanisms of

courts and gendarmerie, how can the intolerant individual or faction be

resisted, beyond simply sending them into exile, suspending their membership or

perhaps, removing them permanently (as in what happened to a particular intellectual hero of mine)?

It seems to me that an inclusive community has two possible

approaches to the problem: one therapeutic and the other preventative. The

first of these would involve rehabilitating the person, explaining what is

required and expected of each member of the community and conversely, what they

can expect from their colleagues or comrades. And if this sounds too much like

the Soviet-era euphemism of re-education, remember that therapy is a

two-way process and in this case, the intolerant individual might, by the persuasive

expression of their views, change the community for better. But that is the

risk we take in any genuine dialogue, the end point is never fixed if entered

into in a spirit of openness; it always involves uncertainty.

However, dialogue requires speech that is respectful and responsible.

Parties must enter into a relationship, giving attention to the other, however

painful this might be. And perhaps most importantly, those who dissent from the

ethical norms of the community must take personal ownership of their views, not

represent them as those of some ill-defined ‘silent majority’ or a vague notion

of ‘tradition’, a vague, intangible legacy of which they are the self-appointed

executors, interpreters and advocates.

And although taking ownership of any counter-cultural opinions always requires

courage, the alternative (anonymous missives or trolling on social media)

precludes the possibility of dialogue, an encounter that, given trust, openness

and indeed, the admission of a grain of doubt, can recast conflict as the

engine of ethical and spiritual growth. Writing poison pen letters or graffiti

on lavatory walls – that ain’t it!

And as for prevention? Communities need to make their values explicit and

understood. Like the ancient biblical tradition of Hakhel, reading the Torah to the people every seven years, there must be some contractual mechanism beyond checking the box stating ‘I

agree to the terms and conditions.’ Such a procedure or constitution would hold

members, both new and old, to broad, fundamental principles to which they have

given considered and explicit consent. These values will always undergo

editing, revision and redefinition, deletions and additions. But by stating

clearly the boundaries of where a community stands, even while positions are

shifting, the community enables new entrants to make an informed choice as to

whether they want to come inside.

Living Community

A community whose collective opinions are frozen in time is dead, its

life-blood clotted. This is not to say that everything is negotiable. I happen

to believe that intolerance, homophobia, racism and xenophobia are wrong. So I

choose to belong to groups defined by how they surpass even the ideal of

tolerance, valuing acceptance and celebrating a diversity that is the warp and

the weft, the secret of the strength of such communities. But if we give up on

the messy and sometimes painful business of dialogue, either by stepping

outside and throwing rocks in or by excluding the difficult person who perhaps

just doesn’t know how to speak our language, then we condemn the community to

atrophy and death.

Since I started to write this post I have seen the opening up of new and

bitter division both within the Anglo-Jewish community and beyond. People are

told they are either with us or against us, but this is a classic

all-or-nothing fallacy: in many cases the binary is artificial, ignores

gradation, nuance and perhaps mischaracterises certain pairs of viewpoints as

polar opposites when really they have more in common.

Can we take a stand, bravely and respectfully remaining in dialogue

with those who disagree with us? Have we the courage to choose to be part of

the cut and thrust, the ebb and flow that makes for a living, breathing

community? I hope that we will choose wisely, choosing life so that we, our

communities and our children can live.

Now read on

- Sheila Shulman, Watching for the Morning: Selected Sermons (London: BKY) 2001

- Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies (London: Routledge) 1995

An example of a Community Ethos for the Jewish Community founded by Rabbi Sheila Shulman can be found at https://www.bky.org.uk/ethos

For reasons that will become apparent, I’m contemplating the idea of emptiness at the moment. And perhaps something more empty than emptiness, more absolute than mere negation, more devoid of anything and everything than just void.

For reasons that will become apparent, I’m contemplating the idea of emptiness at the moment. And perhaps something more empty than emptiness, more absolute than mere negation, more devoid of anything and everything than just void.